Fake news is not new to Nigeria. In the 2015 elections, for example, a 55-minute documentary full of falsehoods entitled “” aired on television before doing the rounds on social media. In 2017, Biafra separatists attempting to disrupt the Anambra governorship vote the army was injecting school students with monkey pox to depopulate the South East, leading some schools to close and parents to withdraw their children in .

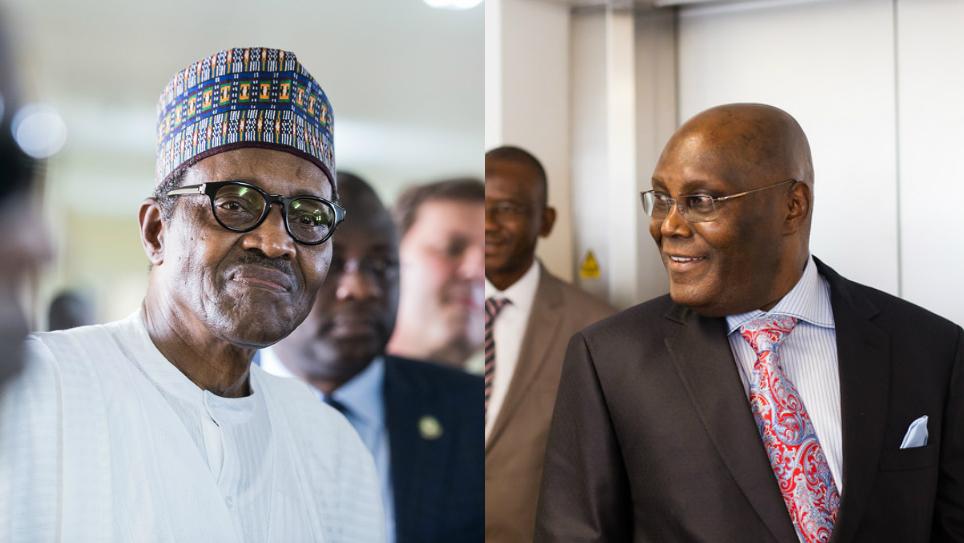

This phenomenon has reached new heights, however, ahead of Nigeria’s 2019 elections. As the campaign has heated up, fake news about both President Muhammadu Buhari and his main opponent former vice-president Atiku Abubakar has swirled on Whatsapp, Facebook and Twitter. It has been shared knowingly by canny campaign officials as well as unwittingly by thousands of unsuspecting voters.This false information covers many topics and takes different forms. On the subtler end of the scale, there are examples such as Buhari’s aide saying that Atiku only avoided arrest on his US visit because of diplomatic immunity; or the opposition official posting news that “800 companies shut down” even though the story pre-dated Buhari’s term. On the wilder end of the scale, there are the claims that President Buhari has been replaced with a Sudanese clone; or that Kim Jong Un wants to re-colonise Nigeria.

There is also much in between and, together, these stories have spread far and wide. Many have taken on lives of their own. This has created an ever-more uncertain and heightened atmosphere ahead of Nigeria’s high-stakes elections.

How fake news works in Nigeria

False information in Nigeria spreads through various channels, but social media provide the cheapest and quickest ways to access millions. Through Whatsapp and Facebook, people share propaganda videos, made-up quotes, and fabricated articles made to look like they are from the likes of the BBC or Al-Jazeera. Meanwhile on Twitter, bots and trolls working for both Buhari and Atiku’s camps amplify false stories and contribute to the polarisation of the discourse through bullying and intimidation.

Disinformation also operates offline. Mainstream television and radio stations, for example, frequently host “political consultants” – or Sojojin Baci (“soldiers of the mouth”) as they are known in the North – who further spread half-truths and manipulations in favour of their candidates. Often online and offline routes work together. A rumour that begins on social media may be taken up by the Sojojin Baci through more traditional media, who can add nuance to the story in a way that allows it to resonate with a new audience.

More examples of fake news in which stories have been fabricated to look like they are from mainstream news sources.

The effects of disinformation

It is perhaps too early to assess the impact of all this fake information on Nigeria’s 2019 elections. But earlier instances of false stories spreading may be instructive.

During the West African Ebola outbreak in 2014, for example, a story circulated claiming that a local leader in Kogi state had on all members of the Igala people to bathe in salt water to avoid infection. The false report was first disseminated on Whatsapp and by phone. Then, it was picked up by radio and television stations. Soon, the notion that bathing in salt water protects against Ebola had spread well beyond the Igala people and Kogi state. Hundreds of miles away in Plateau state, for instance, at least two people and another two were hospitalised after excessively consuming salt and bitter kola believing it would defend them against the Ebola.

At the moment, the single most widely-disseminated piece of fake news is the claim that President Buhari has been replaced with a Sudanese clone named Jubril. The allegation was first presented in a YouTube video made by Nnamdi Kanu, leader of Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), in September 2017. The assertion was widely repeated over the following months, though most observers dismissed it as a joke. However, as the election has approached, it has become apparent that several segments of society genuinely believe the false rumour. It has become so serious that President Buhari felt to need to confront it directly in December 2018 both through a press release and by publicly “It’s the real me, I assure you”.

The fact that such an outrageous rumour can reach these levels of dissemination and be believed widely speaks to the potential and dangers of fake news.

The aim of fake news

Disinformation campaigns are run for a variety of purposes. In an election season, they are typically geared towards garnering more votes, dividing the electorate, or suppressing votes for one’s rivals.

An example of this latter strategy may be visible in the emergence of a faceless group calling itself the Fulani Nationalist Movement (FUNAM). It is unclear who is really behind it, but the group is fuelling ethnic and religious tensions through hate messages. It is calling on people to boycott the upcoming elections and to look forward instead to a time when Muslims will rule forever.

Fake news is a huge concern ahead of the Nigerian elections and shows no signs of letting up or being tackled. This is worrying as disinformation is provoking animosity along religious, ethnic and regional divides which are often already tense. It is increasing distrust in both specific candidates and the process as a whole.

Election season is in full swing in .

In the presidential contest, we now know it will likely be a straight contest between incumbent Muhammadu Buhari of the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) and challenger Atiku Abubakar of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP).

Dozens of other candidates will be competing. These include: Oby Ezekwesili, the former minister and founder of the Bring Back Our Girls movement; Professor Kingsley Moghalu, the former deputy governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria; and Omoyele Sowore, the owner of the media outlet Sahara Reporters. But when it comes down to it, it will be a two-horse race.

This will not be the first time Buhari, 75, and Atiku, 71, have faced one another. Both men contested the 2007 presidential elections, coming a distant second and third behind the PDP’s Umaru Yar’Adua. In 2014, the two met again in the APC primaries, with Buhari emerging victorious.

These past races offer little guidance, however, for how the 2019 presidential election between these two gladiators of Nigerian politics might play out.

There are two ways of assessing their chances of electoral success: by looking at the main issues and where they stand on them; and by looking at the electoral maths required to win and seeing how they are each faring.

The issues voters may have concern:

First, the issues. Nigerian voters have many concerns, but for many, the key concerns are the same three that dominated the 2015 elections.

Corruption

In 2015, Buhari drew heavily on his reputation as incorruptible as he vowed to root out corruption. In 2019, he will undoubtedly reiterate this promise and has some things to boast about. His government claims to have recovered ($2.75 billion) in stolen assets. It has made giant strides in implementing the Treasury Single Account (TSA) to reduce leakages. And it has overseen the of two former governors.Many, however, see President Buhari’s war on corruption as disappointing. In particular, critics accuse the government of only targeting political opponents, while allowing its cronies to go scot-free.In this campaign, though, the ruling APC has a clear advantage on this issue. The PDP is remembered for plundering the state during its previous sixteen years in power. Meanwhile, its flag-bearer, the former vice-president from 1999 to 2007, is one of the country’s richest politicians and has faced several allegations of fraud. In some circles, Atiku’s very name is synonymous with high-level graft.

Many of the fiercest accusations against the PDP candidate have come from former president Olusegun Obasanjo. After the two fell out dramatically in 2006, Obasanjo repeatedly insisted that his former deputy was corrupt and unfit for office. That was at least until a few weeks ago, when Obasanjo changed tack. It remains to be seen if this reconciliation will alleviate the heavy cloud of corruption hanging over Atiku’s head.

Economy

Buhari’s main challenge in office has been the struggling economy, which plunged into recession in 2016. It has since recovered, but growth remains slow. Before Buhari took office in 2015, one US dollar bought between N199 and N220. It recently stabilised at around N360, having soared to an all-time high of N450.Given this context, Atiku is promising to revitalise the economy and emphasising his experience. Atiku has business interests across Nigeria and claims to have provided indirect jobs. He will likely talk up the fact that he oversaw the privatisation efforts under Obasanjo, though the APC may respond by claiming Atiku fraudulently enriched himself through this same process.

His selection of Peter Obi, former Anambra state governor and an astute business man, as his running mate further boosts his economic credentials. Meanwhile, his related promises to restructure the federal system and devote a minimum of 21% of the budget to education may also win him some supporters.

For Buhari, the economy may be a weakness. But he will also have the advantage of incumbency. His administration is currently implementing social intervention programmes said to be touching the lives of thousands. In recent months, it has also launched a collateral-free for micro-businesses, which could win sympathies among many nationwide.

[Security

In office, President Buhari has made significant progress combating Boko Haram. The insurgents previously controlled a sizeable portion of the North East, but are now a weakened force. Buhari is lauded for his actions in this area, but Atiku may also seek credit for mobilising hunters to wade off the militants in his native Adamawa.While the threat from Boko Haram may have diminished to an extent, however, insecurity pervades much of the rest of the country. Nigeria faces the escalating , , and to name a few. Buhari has been seen to be slow to respond to many of these threats and has been accused of only caring about issues that affect his own ethnic group.

Electoral maths

Atiku can mount a serious challenge in the 2019 elections. He is up against a candidate who spent seven months in treating an undisclosed ailment and whose national approval rating is at just 40% according to Buharimeter. The PDP challenger can also rely on the full party machinery now he has won the primaries and draw on the influence of party stalwarts. Meanwhile, the formation of the opposition (CUPP) means there will be fewer candidates to split the anti-APC vote.

That being said, the incumbent has the advantage. In 2015, Buhari won by a significant margin of 2.5 million votes. Although his record in office has been mixed, 2019 looks like his election to lose.

Below is a breakdown of the race in Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones. For context:

- There are currently 84,271,832 nationwide.

- In 2011, Buhari got 12.2 million votes (32%) to Goodluck Jonathan’s 22.5 million (59%).

- In 2015, Buhari got 15.4 million votes (54%) to Jonathan’s 12.9 million (45%).

North West

- 2011 results: Buhari, 6,453,437 (60.43%); Jonathan, 3,466,924 (32.46%).

- 2015 results: Buhari, 7,115,199 (81.34%); Jonathan, 1,352,071 (15.46%).

- 2019 registered voters: 20,122,934 (as at August 2018).

President Buhari is adored by peasants in northern Nigeria. He is popularly referred to by them as Mai Gaskiya, which translates roughly to “trustworthy” in Hausa. According to a source, the more Buhari is criticised, the more people in the north love him.

The North West, by far Nigeria’s most populous zone, is particularly strong Buhari territory. In both 2011 and 2015, he won all seven states. His approval rating here is 58%.

Kano state alone has 5,462,898 registered voters (as at August 2018), making it the country’s second biggest voting bloc after Lagos. Governor Abdullahi Umar Ganduje wields extensive influence in this state and has promised Buhari a gargantuan votes in the presidential poll. The governor already delivered votes for Buhari in the APC’s questionable primaries.

There are a couple of factors going against the APC, however. Firstly, the conduct of the APC primaries has created some discontent within the party. And secondly, former Kano governor Rabiu Kwankwaso, who helped Buhari win big in 2015, has defected to the PDP and declared his full support for Atiku.

North East

- 2011 results: Buhari, 3,660,919 (63.42%); Jonathan, 1,832,651 (31.75%).

- 2015 results: Buhari, 2,848,678 (75.28%); Jonathan, 796,588 (21.05%).

- 2019 registered voters: 11,170,847 (as at August 2018).

Buhari is similarly well-liked in the North East, where he is credited with suppressing Boko Haram and bringing normalcy to Adamawa, Borno and Yobe states. This zone has also benefited significantly from patronage politics under Buhari, who has recruited many of his top lieutenants from the North East. His approval rating here is 57%.

Atiku is from the North East, specifically Adamawa state. He also has some important allies in the zone. In Gombe, Governor Ibrahim Hassan Dankwambo will help him win votes. And in Taraba, former minister Aisha Alhassan will also exert her influence in Atiku’s favour having recently walked out of the APC.

Helped by popular frustrations at Taraba’s ongoing insecurity, Alhassan’s extensive influence means she is likely to help maintain the PDP’s record of winning this state. However, Atiku faces an uphill battle everywhere else in a zone that voted overwhelming for Buhari in 2015.

North Central

- 2011 results: Buhari, 1,744,575 (31.87%); Jonathan, 3,376,570 (61.69%).

- 2015 results: Buhari, 2,411,013 (56.24%); Jonathan, 1,715,818 (40.03%).

- 2019 registered voters: 13,333,435 (as at August 2018).

The North Central zone is traditionally Nigeria’s swing region. In 2011, Buhari only won in Niger state. In 2015, he won four states – Kwara, Kogi, Benue and Niger – and lost in relatively close races in Plateau, Nasarawa and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Abuja.

In 2019, Buhari may find it harder going than the last time. Many people are unhappy with the government’s response to herder-farmer clashes, which have ravaged Plateau and Benue states in particular.

Meanwhile, political realignments in several states could make things tough for Buhari. Two defections to the PDP stand out in particular: Bukola Saraki, the Senate President and former Kwara governor; and Samuel Ortom, governor of Benue. Their switches of allegiance could make this zone more competitive.

South West

- 2011 results: Buhari, 321,609 (7.05%); Jonathan, 2,836,417 (62.22%).

- 2015 results: Buhari, 2,433,122 (53.6%); Jonathan, 1,821,416 (40.12%).

- 2019 registered voters: 16,341,312 (as at August 2018).

The South West will be closely fought. In 2015, the PDP only won one of the six states here, but still managed to get 40.12% of the vote.

Some believe the APC will do better in 2019 than in the last elections. This is in part thanks to Buhari’s decision to posthumously honour MKO Abiola, the winner of the annulled 1993 presidential elections, and move Democracy Day to the 12 June, the date of that vote. Abiola, who grew up in Ogun state, is still celebrated in the South West and around Nigeria. Buhari is also aided by the fact the APC can draw on the influence of all six governors in the South West, the prominent former Lagos governor Bola Tinubu, and his Ogun-born vice-president Yemi Osinbajo.

Some factors could undermine the party’s fortunes, however. The APC primaries have created some disgruntled figures. Many voters see the administration’s performance in the past few years as lacklustre. And the powerful church could yet play a significant and thus far unclear role.

The huge Redeemed Christian Church of God in Lagos may back Osinbajo, which would consolidate support for Buhari. But others like televangelist Tunde Bakare, who first publicly announced the candidature of Oby Ezekwisili, could encourage voters to support her, potentially drawing votes away from the leading candidates.

South East

- 2011 results: Buhari, 20,335 (0.40%); Jonathan, 4,985,246 (98.69%).

- 2015 results: Buhari, 198,248 (7.04%); Jonathan, 2,464,906 (87.55%).

- 2019 registered voters: 10,154,748 (as at August 2018).

The APC and Buhari brands play poorly in the South East and they are even less popular following their handling of the Biafra secessionist movement. Many in the South East believe the region is marginalised, and the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) has been agitating for independence in the past few years. The government has responded heavy-handedly with clampdowns and arrests.

All this means that the PDP is likely to do very well here once again. The fact that Atiku picked Peter Obi, a former Anambra governor, as his running mate will further attract support.

The downside for the PDP is that the South East is the zone with the fewest registered voters, accounting for just 12.04% of the nationwide total. Turnout also tends be low. In 2015, it was just 39% in this region, and it could remain low especially with IPOB calling on supporters to boycott all elections until the government agrees to hold a referendum on independence.

South South

- 2011 results: Buhari, 49,978 (0.79%); Jonathan, 6,128,963 (96.92%).

- 2015 results: Buhari, 418,890 (7.96%); Jonathan, 4,714,725 (89.66%).

- 2019 registered voters: 13,148,556 (as at August 2018).

The South South will also largely back the PDP as it did overwhelmingly in 2011 and 2015. The region – and in particular the populous Rivers state – will likely be a vote bank for Atiku. In these efforts, the party will be aided by Nyesom Wike, the Rivers state governor, a powerful PDP mobiliser.

Buhari will not mount a serious challenge to Atiku in the South South. But he might expect his meagre 7.96% vote share from 2015 to increase following the defections of two former governors – Akwa Ibom’s Godswill Akpabio and Delta’s Emmanuel Uduaghan – to the APC.

No comments:

Post a Comment