What we can learn from Congo election fiasco where Kabila failed ?

Fayulu speaking with Journalist pictured above refused the results

President Kabila in September he restructuring the army and putting his loyalists in command. It is a sign he means to stay on, come what may A sweeping restructuring of the army command is the strongest sign yet that President Joseph Kabila Kabange plans to ignore the constitution and seek re-election for a third term in 2016. The 18 September shake-up of the Forces armées de la république démocratique du Congo (FARDC) means that the military will now be organised in three broad defence zones, in the west, south and east, rather than in eleven commands, one for each province. Kabila has promoted some of his closest allies to head the three zones.but by suprize Kabila choosed one of his friend to be his candidate Emmanuel Shadary

Martin Fayulu enjoys a brief triumph as presidential candidate on a unity ticket before the opposition coalition splinters

The leader of one of Congo's smallest parties, Martin Fayulu, was the surprise pick of opposition factions meeting in Geneva on Sunday (11 November) to decide who should represent them in elections due on 23 December. Fayulu, whose career in business includes 20 years as an executive with ExxonMobil in the United States, is little known outside Kinshasa.

Less than a day after that meeting one of the front-runners for the opposition, Félix Tshisekedi, had withdrawn from the coalition under pressure from grassroots activists in his Union pour la démocratie et le progrès social (UDPS). The other front-runner, Vital Kamerhe, leader of the Union pour la Nation congolaise (UNC), will probably follow suit. Both men are set to pursue their own campaigns, splitting the opposition vote. Fayulu was a surprise choice although he has a strong record of activism – he has marched at the head of columns of demonstrators in Kinshasa. That may have helped his cause in Geneva. He also benefitted from support from Jean-Pierre Bemba and Moïse Katumbi – two other potential contenders who were disqualified by President Joseph Kabila's government.

In telephone polls in September, the Congo Research Group based at New York University found that Félix Tshisekedi was by far the best-known opposition politician, with 36% of voter support, and the one to most likely to beat Kabila or his chosen dauphin, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary. Kamerhe scored 17%, with Fayulu in fourth place with 8%.

Fayulu will struggle to bring together all the opposition groupings on the platform known as Lamuka. And with less than six weeks to polling day, he has little time to build up momentum.

There are technical issues to be resolved. The most important is the opposition's refusal to accept the use of sophisticated voting machines imported from South Korea. Fayulu opposes them, unless clear safeguards are put in place. Negotiations between the opposition and the electoral commission on the issue have been stalled for several weeks.

The leader of one of Congo's smallest parties, Martin Fayulu, was the surprise pick of opposition factions meeting in Geneva on Sunday (11 November) to decide who should represent them in elections due on 23 December. Fayulu, whose career in business includes 20 years as an executive with ExxonMobil in the United States, is little known outside Kinshasa.

Less than a day after that meeting one of the front-runners for the opposition, Félix Tshisekedi, had withdrawn from the coalition under pressure from grassroots activists in his Union pour la démocratie et le progrès social (UDPS). The other front-runner, Vital Kamerhe, leader of the Union pour la Nation congolaise (UNC), will probably follow suit. Both men are set to pursue their own campaigns, splitting the opposition vote. Fayulu was a surprise choice although he has a strong record of activism – he has marched at the head of columns of demonstrators in Kinshasa. That may have helped his cause in Geneva. He also benefitted from support from Jean-Pierre Bemba and Moïse Katumbi – two other potential contenders who were disqualified by President Joseph Kabila's government.

In telephone polls in September, the Congo Research Group based at New York University found that Félix Tshisekedi was by far the best-known opposition politician, with 36% of voter support, and the one to most likely to beat Kabila or his chosen dauphin, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary. Kamerhe scored 17%, with Fayulu in fourth place with 8%.

Fayulu will struggle to bring together all the opposition groupings on the platform known as Lamuka. And with less than six weeks to polling day, he has little time to build up momentum.

There are technical issues to be resolved. The most important is the opposition's refusal to accept the use of sophisticated voting machines imported from South Korea. Fayulu opposes them, unless clear safeguards are put in place. Negotiations between the opposition and the electoral commission on the issue have been stalled for several weeks.

The National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI) finally official but provisional results from the Democratic Republic of Congo’s presidential elections held on 30 December 2018. Against all available independent evidence, CENI announced Felix Tshisekedi of the opposition Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social (UDPS) as the winner with 38.5%. Martin Fayulu, of the Lamuka opposition alliance, was said to have obtained 34.7% of the votes. The regime’s candidate, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, garnered 23.8%. The participation rate was 47.6%.

While rumors of a possible Tshisekedi victory had been swirling around the capital Kinshasa over the last few days – fed in part by alleged negotiations between his camp and the regime as well as the candidate’s recent benevolent declarations towards the outgoing President Joseph Kabila – the results are nonetheless highly implausible. Broadly reliable polling data by Congo’s BERCI and France’s IPSOS for the Congo Research Group (CRG) in December and actual voting count data by some 40,000 observers from the Catholic Episcopal Commission (CENCO) point instead to a solid and statistically robust victory by Fayulu.

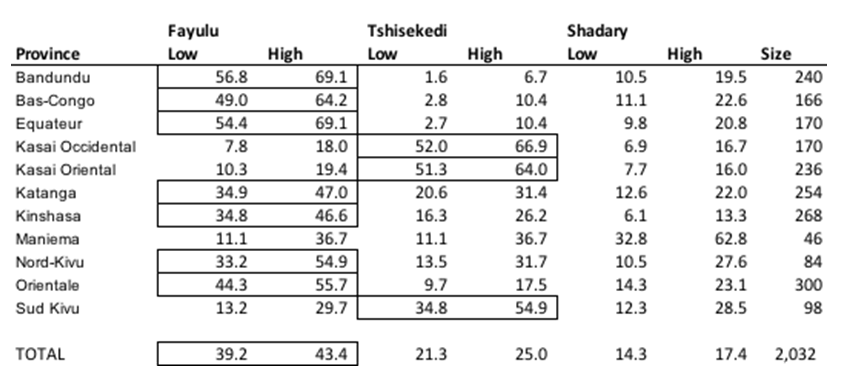

As a matter of fact, and as explained in detail below, CRG’s data suggests that the probability Tshisekedi could have scored 38% in a free election is less than 0.0000. There is a 95% chance his real numbers would be somewhere between 21.3% and 25%.

Even if we include all the people who intended to vote for his ally Vital Kamerhe and attribute all the non-responses in the polls (the 10% who replied “don’t know,” “refuse to answer,” etc.) to Tshisekedi, his 95%-confidence interval would rise to 31.5%-35.6%. There would still be a virtually zero chance he would have got 38.5%.

By that same token, the polls suggest Fayulu would have obtained between 39% and 43% (not 34.7%) of the vote, and Shadary between 14% and 17.4% (not 23.8%). How are these very large discrepancies possible? I review some possible explanations below. But first I revisit the polling data to make sure it is reliable.

Assessing the polls

I obtained the polling data from CRG Director Jason Stearns. In order to reduce margins of error, I pooled the data from both polls into one data set, which totals 2,032 observations. My estimates differ from those published by CRG because some data was missing from the IPSOS file I received and I did not remove the non-answers from the sample. As mentioned above, I addressed the non-answer problems by imputing them all to Tshisekedi. The missing data came mostly from Maniema and, less so, the Kivus. In the poll, Maniema leaned strongly in favor of Shadary, whose home province it is, and South Kivu to Tshisekedi (thanks to his ally Kamerhe who is from there). As a result, greater sample sizes in these provinces would have been unlikely to benefit these two contenders.

CENI has not so far released results by provinces, but presenting the polling data along provincial lines helps make sense of the findings. I use the 11 old provinces (some of which were broken up into smaller units in 2015) in order to have large enough sample sizes.

As the table below shows, the results by province leave little room for ambiguity. Fayulu had a statistically significant lead in seven of them (marked in the table by a box). Tshisekedi had a similar lead in both Kasai provinces and in South Kivu thanks to Kamerhe (who can expect to be rewarded). Shadary had a non-significant lead in Maniema.

But were these polls truly representative? Kabila allies suggested that predictions of a Fayulu victory neglected rural areas where the regime is more popular. However, I did not find any evidence of such a sampling bias. In fact, the joint proportion of urban respondents in both surveys was 41.75%, which is less than Congo’s urbanisation rate of 43.9% according to the World Bank. This suggests that, if anything, rural residents were oversampled.

Despite the relative under-representation of Maniema and both Kivus in the data, the provincial sample sizes still correlated at 0.87 with the CENI figures for registered voters, suggesting the overall representativeness of the results at the national level.

Could BERCI, IPSOS or the CRG have cheated? Some have suggested that BERCI Director Francesca Bomboko is a close friend to Olivier Kamitatu, who used to run BERCI with her and is now opposition figure Moïse Katumbi’s chief-of-staff. Others have pointed out that Stearns is a long-standing critique of the regime, who was expelled from Kinshasa a couple of year ago. Though this may be true, I very much doubt they could have led to fraud. BERCI has a long-established reputation as an independent polling institute and the closeness of its results with those of IPSOS offers prima facie evidence of their validity. Meanwhile, Stearns’ scholarship on Congo has stood out for years for its rigour and independence.

How do we make sense of the results?

How do we make sense of the results?

All in all, it is the Congolese regime that had the greatest incentives to cheat. And there are many indications it did so. I will not focus here on the well-documented repression of the Congolese opposition and the obstacles put in the path of Fayulu’s campaign here; the many instances of dubious practices by CENI and its staff might have been enough to sway the results.

First, there was the suspension of the voting in various places. The election was postponed in Beni territory, Beni town and Lubero territory (all in North Kivu) for Ebola reasons. And it was delayed in Yumbi territory in Mai-Ndombe (ex-Bandundu) province because of intercommunal violence. Fayulu is from Bandundu and, as the table shows, he had a strong lead in North Kivu. This decision removed 1,745,249 registered voters from the poll, a large proportion given that Tshisekedi allegedly beat Fayulu overall by 684,281 votes.

Second, there was the matter of the observation, counting and reporting of votes. Congo’s two-step system is meant to prevent fraud. The 72,458 polling stations are charged with the immediate counting of the votes, in front of witnesses from political parties and observers from civil society (who must sign off on them), as soon as the polls close. They must then physically post the results on location and send them, collated by candidate, to 176 Local Centres of Compilation of Results (CLCR). These centres aggregate the results from multiple stations and communicate them in electronic form to CENI.

In the days following the elections, the Catholic Church under CENCO, which had 39,082 observers in polling stations, and the civil society coalition SYMOCEL, which had observers in 101 CLCRs, made numerous reports of fraud and irregularities. Their officials were often not allowed to witness, some ballots went missing as did some voting machines, and there were reports of inaccuracies between CLCR and polling station tallies (with several instances of CLCR witnesses refusing to sign off on the official counts). Similarly, there was evidence of pressure on voting day. According to CENCO, for example, in only 65% of cases were voting booths placed in a manner that guaranteed secrecy.

Finally, the long delays to present the results (ten days after the elections) were also suspicious. In the end, Nadine Michika, the CENI member from the MLC opposition party, which backs Fayulu, walked out of the CENI plenary session a couple of hours before the results were announced. This was apparently because CENI President Corneille Naanga would not verify the consistency of the CLCR results with the data from the polling stations. If this is indeed the case, it would make a mockery of the legal safeguards against fraud and would partly explain the inconsistency between the CENI’s results and those of CENCO, which were based on the polling station reports. CENCO announced on 3 January that it knew the winner from its parallel counting system but, following the law, did not publicly name the person. Apparently, however, it revealed to diplomats that it was Fayulu. At the time of writing, CENCO had not yet released its data.

Amidst all this, one non-fraudulent possibility is that the election’s participation rates, at 47.6% overall, worked hugely in favour of Tshisekedi. CENI has not so far released province-specific rates, but it is theoretically possible that turnout was massive in Tshisekedi regions and low in Fayulu’s. In terms of registered voters, Tshisekedi’s strongholds of the Kasais contain 3.5 million and 3 million potential votes, while South Kivu has 2.6 million. By contrast, Bandundu has 4.3 million voters, Equateur 4.7 million, Katanga 5.9 million, Kinshasa 4.5 million, Orientale 4.9 million, and North Kivu fewer than 2.8m after the suspension of voting in the Grand Nord. Still, it is mathematically possible (I tried) to have Tshisekedi come out the winner if “his” provinces showed very high participation rates (in the 90%) and Fayulu’s provinces very low rates (some in the 30%) and if Fayulu came out at the low end of his vote range and Tshisekedi at the high end of his. This, however, is empirically extremely unlikely.

But why Tshisekedi?

If the regime cheated, why let Tshisekedi, the son of the late historic opponent Etienne Tshisekedi, win? Here, we can only hypothesise. However, it certainly looks like it would have been all but impossible to tweak, massage or even invent numbers to the scale necessary to give the regime’s candidate Shadary a victory. Even his official result, at 24% already probably padded, is dismal. It means that fewer than one in four Congolese supports the regime, a rejection of stunning proportion for an incumbent (but not a surprise, so incompetent and callous Kabila’s rule has been).

One possibility for today’s result is that once the regime saw the catastrophic mistake Kabila had made by nominating Shadary, it scrambled to come up with a Plan B. Enter Tshisekedi and his accomplice, Vital Kamerhe, a former Kabila ally. The last two prime ministers of Kabila both came from Tshisekedi’s UDPS party. While the party excluded them as a consequence (resulting in as many as four different UDPS factions), Tshisekedi himself has wavered at times in his opposition to the regime and is far from having his late father’s intransigence.

[]

Back in November 2018, Tshisekedi agreed at a meeting in Geneva with other opposition figures to support Fayulu’s candidacy. 24 hours later, he reneged and formed an alliance with Kamerhe. What happened? Some have suggested the regime might have already sought to encourage his defection from the opposition coalition then, but that might not have been necessary. My guess is that Tshisekedi was unwilling to consider anyone but himself as the opposition candidate. When he lost the vote to be the opposition nominee to Fayulu, he may have been unable to back out of it in front of everyone but, once safely away, he could argue that his “base” opposed the deal.

This decision would be rational if Tshisekedi sought to maximise his own political fortunes. He might have thought that, if he backed Fayulu, the latter would win. In this eventuality, Fayulu would probably rehabilitate the two other leading opponents, Jean-Pierre Bemba and Möise Katumbi, whom the regime had prevented from running. This means that, next time around, Tshisekedi would have even less of a chance to win. Running now gave him at least a remote chance of victory, but, more importantly, positioned himself to bargain with the regime.

[

Maybe Tshisekedi anticipated a controversial Shadary victory and saw an opportunity to sell his endorsement of it in exchange for something like the Prime Minister position. Perhaps when the regime ended up in a much weaker negotiating position, Tshisekedi was able to demand the presidency in exchange for letting the ruling Front Commun pour le Congo (FCC) share power with him.

If this was the case, it looks like Tshisekedi’s gamble worked out, so far probably beyond his wildest dreams. But if the history of the Kabila regime and its tight control on the state and its security apparatus are any indication, the DRC’s new president-elect is likely to end up on the losing end of this bargain.

Church claims sweeping opposition win report published on African confidential.

Early results – which the regime is banning the media from reporting – indicate a win for the opposition after government plans to fix the poll went awry

A showdown is looming after the country’s Catholic bishops announced they knew who had won the presidential election on 30 December, as anger builds after delays in the release of official results and the shutdown of national communications.

Congo-Kinshasa’s election body – the Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) – has said nothing so far. CENI president Corneille Nangaa says the publication of preliminary results scheduled for 6 January will be postponed, as tally sheets trickle in to the regional centres for official tabulation.

The Bishops’ Conférence Episcopale Nationale du Congo (CENCO) had organised up to 40,000 election monitors to scrutinise the conduct of the poll and conduct a parallel vote tabulation. CENCO did not name the winning candidate publicly, but declared that he had polled over half of the votes in the presidential election. Martin Fayulu is the unnamed winning opposition candidate, Africa Confidential’s church sources say.

Rival opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi and the ruling coalition candidate Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary are trailing with around 20% each, we hear (AC Vol 59 No 25, The Twelve Fixes of Christmas). All these figures, and the detailed calculations underlying them, were provided by CENCO to diplomats in Kinshasa on 2 January.

On 4 January, Information Minister Lambert Mende summoned the international media to forbid them from reporting results ahead of CENI’s announcement. CENCO’s announcement was a bombshell for President Joseph Kabila, who in August succumbed to pressure to hold long-delayed elections and chose former interior minister Shadary to be the ruling party’s presidential candidate.

Widespread intimidation, suspension of polling in certain areas, and use of government facilities by the ruling party were reported as Kabila’s allies attempted to fix the result in Shadary’s favour. But the fix was not thorough enough, sources in Shadary’s Front commun pour le Congo (FCC) told Africa Confidential. They said control of the poll was lost because they did not pay off enough election officials.

Only CENI, seen as close to the presidency, may announce the result of the presidential and parliamentary elections. By pre-empting it, CENCO makes it harder for CENI to report a result widely at variance with its own. CENCO and the Catholic church, whose congregation comprises about half the population, has been a thorn in Kabila’s side for years. Church observers were present at the country’s 70,000 polling stations on polling day, and when the final results were tallied and printed out by electronic voting machines.

On 31 December, the government shut down internet services across the country, ostensibly to prevent the circulation of ‘fake’ results. Fayulu stated this was done to stop the opposition broadcasting its ‘overwhelming victory’.

CENCO played a prominent part in opposition politics; the church joined the peace marches of 1992 which began the process of toppling the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, and in the protests last year against the postponement of elections which were put down with much loss of life.

The national army, the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo, and the Police Nationale Congolaise (PNC) deployed up to 15,000 newly-recruited troops around the country to provincial hotspots such as Ituri, North Kivu, South Kivu, the Kasaïs, and Kinshasa to quell any unrest that might meet an unpopular announcement by CENI (AC Vol 59 No 17, Kabila's two-front offensive).

The Synergie des Mission d’Observation Citoyenne des Élections (SYMOCEL), a civilian observer coalition with more than 18,000 monitors throughout the country, reported that although the elections were broadly peaceful, there had been illegal replacements and widespread breakdowns of electronic voting machines.

SYMOCEL reported that 24% of the polling stations it observed closed before those already in line were able to vote, and voting centres were relocated by CENI at the last minute, confusing voters who could not locate themselves on voting lists. Some 27% of the polling stations opened late, 18% suffered from malfunctioning voting machines, and 15% did not publicly display vote tallies after counting as required by law, SYMOCEL added.

Meanwhile, according to United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission (Monusco) sources, Shadary relied extensively on armed groups to deliver him the vote in North Kivu – the second biggest province for registered voters after Kinshasa and one of the most troubled by militia activity and mining for ‘conflict minerals’. One of Shadary’s helpers was Nduma Défense du Congo – Renové (NDC-R), led by Guidon Shirimay Mwissa, who was put under UN Security Council sanctions in February 2018, according to the sources.

The United Nations has been playing down such concerns and giving the regime an easy ride on its efforts to manipulate the elections, its critics say. The UN’s head of peacekeeping operations, Jean-Pierre Lacroix, told the UN Security Council there were only ‘rare instances’ of delays at polling stations and failed to mention pro-FCC ballot-stuffing, we hear.

Monusco chief representative Leila Zerrougui instructed her staff to stay away from polling stations on election day and did not protest CENI’s decision just days before the election to cancel polls in the opposition strongholds of Beni and Butembo on the pretext of an Ebola and security crisis. Voters turned out anyway in their tens of thousands to hold mock elections in these locations.

Diplomats and officials of the African Union, which deployed an election observer mission, admit in private they are convinced that Fayulu has won. The US and some European governments are pressuring South Africa and Angola to discourage Kabila from fixing the poll results and declaring a Shadary victory, which would spark mass protests.

This week, Monusco has been documenting cases of CENI officials printing ballot-papers on printers in private locations. The US Department of State issued a statement on 3 January reminding Kinshasa of the AU’s call for the official results to align with the actual votes cast and that ‘those who undermine the democratic process, threaten the peace, security or stability of the DRC, or benefit from corruption may find themselves not welcome in the United States and cut off from the US financial system’.

What do the neighbours think?

Many of the thousands of new troops deployed across Congo-Kinshasa to suppress potential post-election violence, especially in the case of a victory being declared for ruling party candidate Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, are ex-members of the disbanded pro-Rwanda militia, the Mouvement du 23 mars (M23) Kinshasa military sources say.

Diplomats from the region told Africa Confidential that the vanguard of the recent intake to the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo were ex-M23 fighters handed to FARDC by Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame. The diplomats say Kigali supports President Joseph Kabila’s plan to install Shadary because this may be the best way to maintain Rwanda’s leverage over Congo-K’s institutions and army, and so control conflict on Rwanda’s western border.

Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni is apparently unhappy with this plan, and his intelligence operatives have been infiltrating ex-M23 and other fighters still hostile to Kabila and Kigali into the Ituri and the Beni areas to oppose the FARDC contingents there.

Sources close to the Rwandan government say they have evidence that a cross-border December attack from Congo-K which killed at least two Rwanda Defence Force soldiers was led by the mainly Hutu militia, Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR), working alongside the Rwanda National Congress (RNC) opposition rebel group of General Kayumba Nyamwasa, the exiled general who is based in South Africa and who Kigali believes now to be working with Kampala.

Kigali’s backing of Kabila’s succession plan is fragile, however, given that the RNC is believed to have hundreds of fighters in South Kivu who are tolerated, if not more, by the FARDC. In his New Year television address, President Kagame criticised two unnamed neighbouring countries for supporting both the FDLR and RNC which no local diplomats doubt are Burundi and Uganda.

|

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2019

https://www.africa-confidential.com

https://www.africa-confidential.com

No comments:

Post a Comment