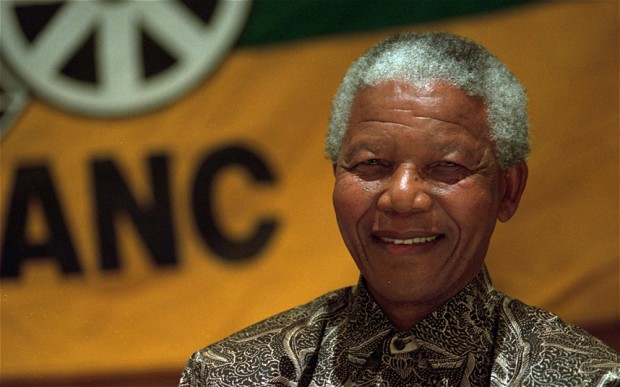

MADIBA was not a saint. We would dishonour his memory if we treated him as if he was one. Like all truly exceptional human beings he was a person of flesh and blood, with his own idiosyncrasies, his own blind spots and weaknesses. He was also a human being who decided to take political action to fight injustice – and in the process sacrificed much in the struggle against racial oppression. It would dishonour the late Nelson Mandela to de-politicise his legacy and to pretend that his life was not synonymous with the ANC (as it then was) and the struggle against white privilege and domination. His brilliance must surely be found in the fact that he was a principled and hard-nosed politician who also had the dignity and the self-knowledge that drove him to try and bridge the unjust divide between races created by colonialism and apartheid. Nelson Mandela was first and foremost one of the greatest if not the greatest leader the ANC ever had. Much of what he did during his life he did in the name of the ANC. This was probably his greatest source of strength.

He was loyal to a fault, writing President Jacob Zuma a R1 million cheque a few days after Zuma was fired as Deputy President. This he did despite the fact that a few weeks earlier a court had found that Zuma’s “financial advisor”, Schabir Shaik, had solicited a bribe from an arms company on Zuma’s behalf and had also paid Zuma more than R1 million to ensure that Zuma would use his political clout to do favours for him in return. In this case Mandela’s loyalty to Zuma (and to the ANC) seemed to have trumped his disgust of corruption and nepotism. Recognising this should not diminish him in our esteem. Instead it should remind us that he was somebody far more interesting and human than a saint. It is exactly because he was very human that his exceptional qualities come into focus so sharply.

He has no excuse, because he is a representative of a discredited regime, not to uphold moral standards. He has handled – and before I say so, let me say that no wonder the Conservative Party has made such a serious inroad into his power base. You understand why.If a man can come to a conference of this nature and play the type of politics which are contained in his paper, very few people would like to deal with such a man. We have handled the question of Umkhonto we Sizwe in a constructive manner. We pointed out that this is one of the issues we are discussing with the Government. We had bilateral discussions but in his paper, although I was with him, I was discussing with him until about 20h20 last night, he never even hinted that he was going to make this attack. The members of the Government persuaded us to allow them to speak last. They were very keen to say the last word here. It is now clear why they did so. And he has abused his position because he hoped that I would not reply. He was completely mistaken. I am replying now. We are still to have discussions with him if he wants, but he must forget that he can impose conditions on the African National Congress and, I daresay, on any one of the political organisations here.

It was exactly because he was so principled and knew what he wanted that as President of the country he could also be remarkably humble and uncompromisingly principled. As President he displayed a majestic sense of right and wrong and an admirable respect for those who were not categorised as having the same race, sex, or sexual orientation than himself. He also reached out at those who are living with HIV.

In this he embodied the principle, first enunciated by the Constitutional Court in the judgment that declared invalid the criminalisation of same-sex sodomy, that equality at the very least demands respect for people who are different from oneself and at best demands a celebration of those differences.

Nelson Mandela’s displayed an astonishing and unique respect for the post-apartheid judiciary. Given the fact that he spent 27 years in jail after being sentenced to life imprisonment by the apartheid judiciary, he might easily have harboured some suspicions against old and new order judges alike. Yet, he understood that the success of South Africa’s new democracy also depended on the very judiciary, which had previously enforced apartheid legislation, often with enthusiasm and without any regard for justice. Speaking at the inauguration of the Constitutional Court in 1995, he said the following:The last time I appeared in court was to hear whether or not I was going to be sentenced to death. Fortunately for myself and my colleagues we were not. Today I rise not as an accused but, on behalf of behalf of the people of South Africa, to inaugurate a court South Africa has never had, a court on which hinges the future of our democracy.

Mandela then continued:People come and people go. Customs, fashions, and preferences change. Yet the web of fundamental rights and justice which a nation proclaims, must not be broken. It is the task of this court to ensure that the values of freedom and equality which underlie our interim constitution – and which will surely be embodied in our final constitution – are nurtured and protected so that they may endure. Given his history, and given the respect he commanded across the political spectrum by the time he became President of South Africa, Mandela could easily have objected when un elected judges of the Constitutional Court first declared his actions unconstitutional and invalid.But this he did not do. Instead, he embraced the principle of constitutional supremacy and set the Constitutional Court on the road to becoming one of the most respected, perhaps even revered, courts in the world.

This happened in 1995, only one year after the advent of the new Constitution, when the newly established Constitutional Court declared invalid a provision of the Local Government Transition Act. The impugned provision bestowed power on the President to amend that Act, which had been duly passed by Parliament. President Mandela had relied on this provision to amend the Act. The New National Party government (who then governed the Western Cape Province) challenged the validity of President Mandela’s decision on various grounds, including on the basis that the provision in the Act on which President Mandela had relied was unconstitutional. The Constitutional Court found that the provision was indeed unconstitutionally because it breached the separation of powers doctrine as it handed over the power to enact legislation to the President while the Constitution reserved this power for Parliament.

After the Constitutional Court handed down this ruling, President Mandela appeared on television to affirm his respect for the power of the Court to declare his actions unconstitutional and invalid. He also affirmed that he would respect and obey the decision of the Court. After all, the power of the Constitutional Court to nullify decisions of the President that did not comply with the Constitution lay at the heart of our system of constitutional supremacy.By affirming that it was necessary for the legislative and executive branches of government to respect and obey the decisions of the judiciary, Mandela confirmed respect for the principle of checks and balances built into the Constitution, making it difficult if not impossible for his successors to question the validity of unpopular court judgments.

It was even more remarkable when, a few years later, a judge of the High Court inappropriately compelled Mandela to testify in open court about the circumstances which led the President to appoint a Commission of Inquiry into the affairs of the South African Rugby Football Union, he complied without fanfare. Despite being the President of the country and despite being Mandela, he agreed to testify and to be subjected to cross-examination. The Constitutional Court later criticised the High Court for subjecting the sitting President to cross examination, calling it an “unusual” decision with “far-reaching implications, particularly because of its impact on the question of separation of powers and the comity between different arms of the state.”

The Constitutional Court could not find any cases in foreign jurisdictions in which a head of state had been compelled to give oral evidence before a court in relation to the performance of official duties. Mandela might well have baulked at being ordered by a High Court judge to give oral evidence and to face cross-examination, but he did not. Mandela was not a saint, but he could well be described as the patron saint of South Africa’s democratic order. By signaling – in both words and deeds – that he respected the system of judicial review and that he accepted the principle that the Constitution does and should limit the powers of the other branches of government, he demonstrated the insight and wisdom of a leader that only truly fortunate nations are ever blessed with.

No comments:

Post a Comment