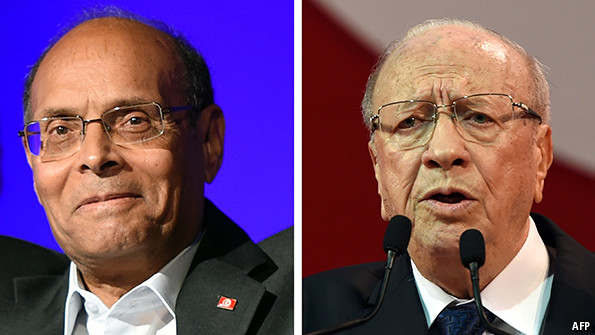

The first round of Tunisia’s presidential election on November 22nd was closer run than most predicted. Only six percentage points separate the frontrunner, Beji Caid Sebsi (pictured above right), the leader of the centrist Nidaa Tounes ("Tunisian Call") party, from Moncef Marzouki (above left), a former dissident. Mr Caid Sebsi, who turns 88 on November 29th, won 39.5% of the vote, and Mr Marzouki, 69, 33.4%. The two will meet for the decisive second round next month.For much of 2011, after the ousting of former president Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, Mr Sebsi served as Tunisia's interim prime minister, before elections in October that year brought Islamist Nahda party to power. Mr Sebsi emphasises his stand against what he views as the Islamists’ attempt to mix religion and politics and promises to “restore the prestige of the state,” which he reckons has been eroded since the ousting of Mr Ben Ali. Nidaa Tounes won the largest chunk of the vote for the assembly last month, ousting Nahda. That means Nidaa Tounes will nominate the next prime minister. By contrast Mr Marzouki, who in 2011 was elected as interim president by the constituent assembly, has portrayed himself as guardian of the revolution, vowing to defend the country's new freedoms. He warns of a risk of backsliding into an authoritarian style of government should one party—Nidaa Tounes—control both the presidency and the prime minister’s office.

Senior members of Nidaa Tounes counter suggestions that they represent a comeback by the old regime by talking about the democratic transitions of Eastern Europe and Latin America. Tunisia, they say, is following a similar path. But they evidently failed to reassure Islamist sympathisers and others who had their liberties severely curtailed under Mr Ben Ali, often through imprisonment and torture. Beefed-up security as Tunisian special forces tackle jihadist groups in the western mountains carries echoes of that time. Some wonder whether new bodies such as a watchdog to prevent torture in detention would stand the test of any swerve towards authoritarian rule.

Younger voters meanwhile were notably absent from the polling stations. The generation that won kudos for taking to the streets against the Ben Ali regime is not apathetic. Debates on social networking sites Facebook and Twitter were so heated in the run-up to the vote that political parties called for moderation. But disappointingly few under twenty-fives were willing to turn up at the sparsely equipped primary school classrooms across the country where voters solemnly cast their ballots. This year, unlike in the vote for a constituent assembly three years ago, voters had to request to be included on the new electoral register. Over half a million fewer voters turned out than in 2011, at around 3.4m of more than 8.2m Tunisians of voting age.The results have exposed a sharp geographic divide, between the more conservative (and poorer) south, where Islamist sympathisers no doubt contributed to Mr Marzouki gaining a large majority of the votes there, and the north, which prefers Mr Sebsi. Mr Sebsi has said that he will now focus his campaigning on the south. He may not go as far as to adopt the burnous—the countryman’s cape that Mr Marzouki affected when he first became president—but he will no doubt emphasise national unity and a commitment to a moderate interpretation of Islam.

Politicians are well aware that the southern and central interior regions have always been the cradle of rebellion, whether in the bread riots of 1983-84, or the 2011 revolution. Meanwhile many Tunisians, both north and south, dismayed by sliding living standards, risk tiring of politics altogether.

No comments:

Post a Comment