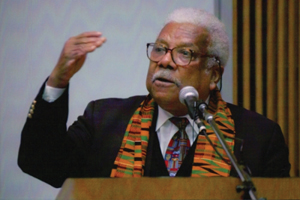

Global African and icon, Ali Mazrui

Professor Ali Mazrui, who died last month at 81 in Binghampton, New York and was buried in the 900-year-old Mazrui cemetery in Mombasa, Kenya, was a polymath, an icon and the pre-eminent African public intellectual. Arguably the epithet "Global African" befits him more than any other African, save Nelson Mandela. His main contribution to scholarship was to make Africa visible in the world of ideas. He did this in public debates as well as in more than 30 books and hundreds of academic papers and articles that he authored.

His zeal in trying to portray Africa correctly was no mean feat considering the obfuscation that has traditionally shrouded the continent as a subject of academic inquiry.

As an original thinker Mazrui's other enduring legacy would be that of a trailblazer, if not the founding father, of global cultural studies. The main thrust of his thought is that the role of culture in shaping political attitudes, in both local and global terrains, has been grossly underestimated. He thus makes us reassess the place of culture in politics and the realities of power in global politics. His was a unique approach to the study of world politics.

In contrast, it was only after the fall of Communism (1989-1991) that Samuel Huntington gained prominence for adopting a theoretical construct on the place of culture in politics.This postulation is not dissimilar to the one which Mazrui had espoused in previous decades, although Mazrui does not concur with the Huntingtonian fatalism of an inevitable clash of cultures or "civilisations", as Huntington called them.

Henry Kissinger, the former US secretary of state, has lately also taken to heart the role of culture in global politics. In his latest book World Order: Reflections on the Character of Nations and the Course of History (2014), he argues forcefully that cultural aspects do shape societies' worldviews.

Some of Mazruis's ideas on culture and politics are encapsulated in his seminal book Cultural Forces in World Politics (1990). Interestingly, they resonate with the thinking of Amilcar Cabral, the Cape Verdean Marxist theoretician who emphasized the role of culture in liberation struggle and in the transformation of society.

Mazrui the thinker was also an activist. As an ardent Pan-Africanist he campaigned vigorously for reparations for Africa and other colonised societies. He played a key role in the holding of the First Pan-African Congress on Reparations that was held in Abuja, Nigeria, in April, 1993.

As a polymath Mazrui's academic interests were wide and varied. Perhaps it was inevitable that as a son of a former Chief Kadhi of Kenya, the distinguished Islamic scholar and writer Sheikh Al'Amin Ali Mazrui, he should devote most of his later works on Islam, particularly its demonisation in the West and how jihadi types have perverted Islamism, as an ideology, and hijacked Islam. He examines all these in his book Islam: Between Globalization and Counter Terrorism (2006).

Mazrui: founding father of global cultural studies

His paper "Africa's Wisdom has Two Parents and One Guardian: Africanity, Islam and the West" (Horn of Africa, 2005, Vol. XXIII, pp.1-36) dwells on a popular Mazruian theme: Africa's Triple Heritage, the influences on Africa of indigenous culture, Islam and the West.

Mazrui popularized the theme outside of academia with a 1986 television documentary series - The Africans: A Triple Heritage - which he wrote and presented.

The series, jointly produced by the BBC and the Public Broadcasting Service in the US, provoked the ire of Reaganites who saw it as being anti-western. That was not the only controversy that courted Mazrui as he has not been without his detractors.As an unabashed critic of Israel's occupation of Palestinian lands he has often incited the wrath of those who confuse anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism.

The Mazrui clan, of which Ali was its most illustrious son, migrated from Oman to East Africa about a thousand years ago. They reigned in Mombasa, the birthplace of Ali Mazrui, in the 18th century and opposed the Al Busaid dynasty that ruled over Zanzibar.

During the early years of British colonialism in Kenya in the late 19th century, the Mazruis, by then fully Swahilised as a result of intermarriage with the local population at the coast, were in the forefront among Kenyans who resisted colonial rule.

Probably it was Mazrui's Afro-Arab heritage that inspired him to pay particular attention to what he considered to be a natural alliance between Africa and the Arab world, an alliance which would eventually lead to the political and economic unification of the two regions. He termed this concept "Afrabia"-a product of Africa's "triple heritage"-as a unit of analysis beyond a purely racial geographical categorization.

Mazrui was inspired by his Afro-Arab heritage

"The concept of Afrabia now connotes more than interaction between Africanity and Arab identity; it is seen as a process of fusion between the two. While the principle of Afrabia recognizes that Africa and the Arab world are overlapping categories, it goes on to prophesy that these two are in the historic process of becoming one," Mazrui wrote.

Mazrui first came to public notice in the early 1960s as an ardent critic of socialism as a vehicle for Africa's development. At the time he was a lecturer, and later professor, of political science at the Makerere campus in Uganda of what was then the University of East Africa. His criticism of socialism went against the grain of the then prevailing African doctrine which veered towards a commitment to "African socialism".

As a result, Mazrui's ideas were ridiculed as a caricature of neo-colonial thinking. His antipathy to socialism was equated to pandering to neo-colonial designs on Africa. But Mazrui was no neo-colonial stooge nor was he an apologist of the western capitalist system which he attacked for exploiting Africa.

People still talk of the grand debates that were held in Makerere and Dar es Salaam University in the 1970s between these two antagonistic schools of thought pitting Mazrui against the pan-Africanist Marxist historian Walter Rodney, the author of How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.

It is ironic that it was Mazrui who was invited to give the inaugural Walter Rodney Memorial Lecture at the University of Guyana and held the first Walter Rodney Chair at the same university.

Mazrui delighted in displaying his verbal dexterity and in using paradox as his main intellectual prop. He was equally adroit in deploying dichotomies and manipulating contrivances to maximum effect in driving home his arguments. Some people confused the lucidity of his speech and writings with the lack of depth. Nothing can be further from the truth. In the future, scholars will turn to his body of work to mine the ideas that he so ably developed.

No comments:

Post a Comment